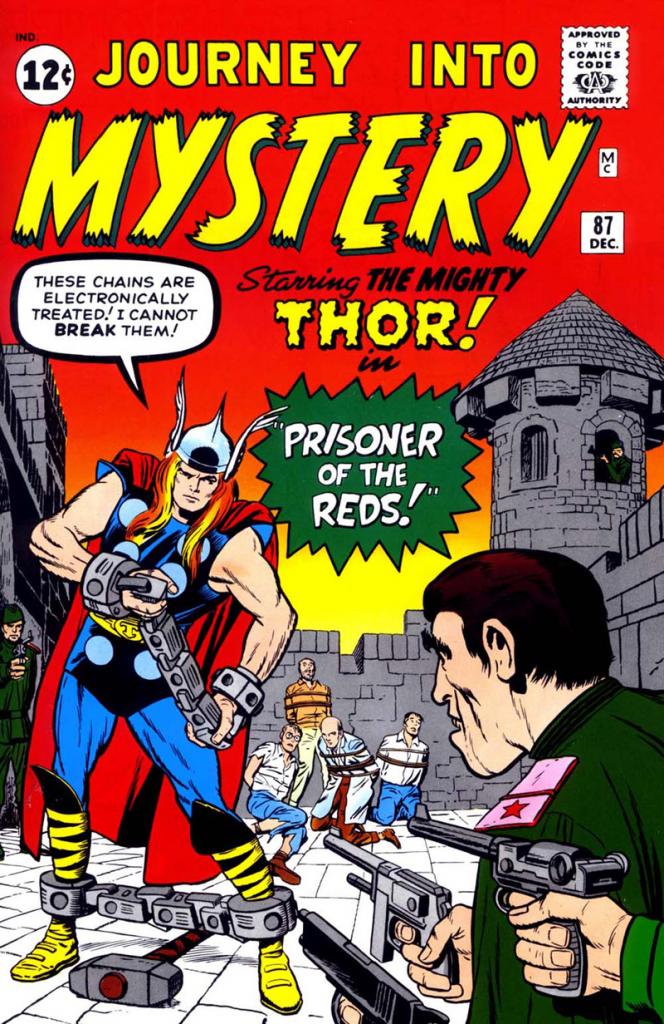

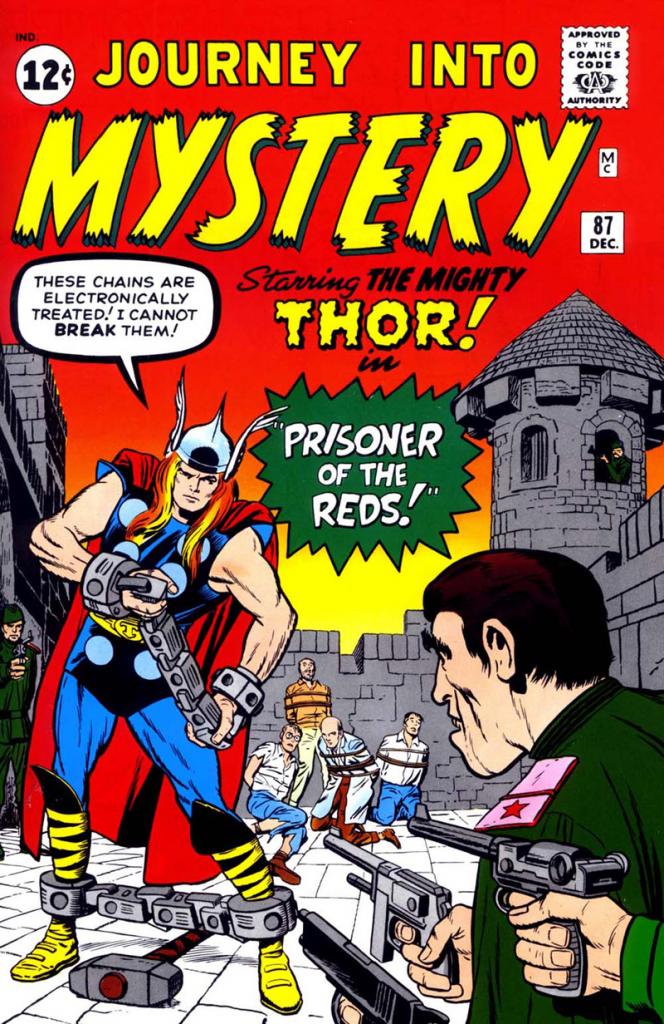

Thor, Norse god of thunder and defender of America against communism... as interpreted by his chroniclers circa early 1960s!

Why Event Accuracy in a Story Can Often be Suspect

by Christofer Nigro

Many thanks go to members of the Wold Newton Beyond group on Facebook for their important suggestions and additional info! I dunno what I would do without those guys!

Thor, Norse god of thunder and defender of America against communism... as interpreted by his chroniclers circa early 1960s!

When research on a particular story is being conducted, how certain can we be that all details are “accurate” within the context of the alternate universe where we presume the events to be taking place in? That actually depends on a variety of factors. Humans have a tendency to err, and authors commonly display this wretched failing of our species in myriad ways when recording fictional events via the written word.

Throughout this essay, I’m going to operate from the conceit that when authors pen a tale, they are subconsciously recording events that “actually” take place in a distant alternate reality. But should we always assume that what those of us on this side of the dimensional wall see when we read or view a story is exactly what “actually occurred” in the alternate universe of note?

For the record, we can most often presume that the basic series of events, and the essence of the dialogue we read or hear the characters utter, are indeed being translated at least close to what “actually occurred” within the context of that other universe. This will vary from instance to instance, of course, based on many factors too complicated to go into here. Of course, since analogues of certain recorded events can occur in multiple different realities—either more or less simultaneously or in disparate time periods--the exact accuracy of the details will vary from universe to universe, specifically tailored to what the physical laws and quantum dynamics of any given universe will allow.

What I specifically hope to describe here are some of the different types of detail errors that can occur when an author on this side of the proverbial fourth wall is filtering them through his/her subconscious mind into a certain storytelling medium.

These detail flubs can commonly fall into the following categories:

Translator Bias: Authors who have loyalty to a specific set of popular political or ideological tenets will sometimes project these loyalties upon a favored protagonist whom they write about. The loyalties of the characters in question can sometimes be deliberately tweaked to make a certain hero more acceptable to readers and publishers of a given place and era; and villains can be similarly tweaked to be loyal to whatever tenets were considered antagonistic to that which the locale and era in question considered to be “the enemy.”

Let’s take a look at some examples:

Note how Captain America was depicted as a gung-ho patriot in the original comic books published during World War II. Then, compare that interpretation of the character to the following words of the cinematic version in his first film, produced circa 2012, after Prof. Erskine asked him if he was ready to kill Nazis: “I don’t want to kill anyone. I just don’t like bullies, no matter where they’re from.”

Note how Thor was depicted in the comics during the 1960s as fully trusting of the United States government, to the point of helping them test weapons of mass destruction for their use against the communists (e.g., the story from Journey Into Mystery Vol. 1 #86). Now contrast that to the frequent adversarial role he has taken towards government and corporate authority in recent years, and particularly the overtly socialist depiction of the thunder god in his ‘Ultimate Universe’ incarnation.

It can be argued that Thor's very contrasting appearance under the Ultimate Comics banner compared to his 1960s portrayal in Marvel's main line of comics was simply due to being a different dimensional version of the thunder god. Personally, I believe there is more to it than that for the following reasons. In Norse mythology, Thor was considered a protector of all Midgard, and specifically the hero god of the common person, not connected to or identified with the ruling class of society. This, IMO, makes it more likely that the mainstream Marvel and WNBU versions of the thunder god would not be likely to ally so closely with the specific interests of the U.S. government against the "reds" as interpreted by the creative staff of Marvel during the early 1960s. I would theorize that the respective analogues of the "actual" situation in both universes wasn't nearly so patriotically correct, and there was a better defined reason for the thunder god to be siding with the American forces that went beyond the mere fact that they were American, and that the opposition was Stalinist.

I also make the above argument because the mainstream version of Thor, as well as his cinematic version, have made it clear that they only side with a governmental entity, such as S.H.I.E.L.D., if the latter's immediate agenda encompasses an apolitical goal of protecting human life anywhere in the world from deadly menaces that threaten large portions of humankind. The Marvel Universe [MU] Thor's lack of fealty to American corporations has been made clear in the past few years with his virulent opposition to Marvel's nefarious mega-corporation Roxxon. I believe the mythological aspects of the thunder god throughout human history make it likely that the 1960s interpretation was based on this type of translator bias, with recent years being closer to "accurate," with the Ultimate Universe [UU] portrayal being closer still, for the above reasons. It's my contention that the WNBU version of Thor combines character and situational elements of the mainstream Marvel Universe [MU] and UU depictions of Thor. For more on the WNBU version of Thor, see my article on him elsewhere on this site.

Note how Iron Man, as published during the 1960s, did no soul-searching whatsoever about creating weapons for the U.S. government to use against other nations during the entirety of that decade of published stories, and was firmly anti-communist and supportive of a strong mutually profitable alliance between American corporations and American government. Now contrast that to how his soul-searching over the matter of profiting over the production of munitions became a major aspect of his character profile in the subsequent decades, including his cinematic version, going so far as to end his contracts for weapons production to both the U.S. government and S.H.I.E.L.D.This more recent popularization of nuance in Tony Stark's character is reflective of the greater acceptance of "gray" ideology and nuance amongst American audiences. This culturally broad change in acceptance of depth in character and societal analysis resulted in the relaxation of the stringent insistence of authors and/or publishers and producers in glamorizing or canonizing any type of action that is done by or for the American military-industrial coalition; and in demonizing any foreign entity who exists outside or (more often) in direct opposition to that structural framework for any given reason.

Why do I opine that the more nuanced portrayals of both heroes and villains, as well as political and corporate entities, are more likely to suggest something at least closer to accurate depictions of the "actual" events being chronicled, as opposed to a one-dimensional approach based solely upon nation or ethnicity of origin? Because I believe that it's well known that human beings in general tend to be multi-faceted considerably more often than unswervingly noble or vile, and organizations and nations are run by human beings, with agendas often dictated by overriding material concerns that trump any type of raw ideology. This is readily observable with the most casual sociological studies of the population of any given nation.

Note how during the 1960s, the original Star Trek series very clearly presented the Federation as a proxy for an idealized America, and the Klingon Empire as a proxy for an unequivocally evil Soviet Union/”red” menace. Then observe how much more nuanced both the Federation and the Klingons were treated from Star Trek: The Next Generation onwards, produced two decades later; and how the Romulans largely became a proxy for fascism in general rather than any specific nation on late 20th/early 21st century Earth.

For example, this is why so many characters translated into tales published or produced in the America of our world during the 1950s and ‘60s were interpreted as being all but blindly loyal to American policies and virulently anti-communist. Communist characters were invariably depicted as one-dimensional villains who often lacked any complex character traits beyond a megalomaniacal desire to destroy “freedom” and dominate the world.

In more liberal places and eras, however, both protagonists and antagonists are allowed to display more nuance and complexity of character. Hence, what we see in tales written during such locales and eras may constitute details that are much closer to what “actually” occurred.

Personal Authorial Biases: In some instances, an author will deliberately introduce their own biases into a story. This can easily taint their interpretation of the events which they are hypothetically "filtering" through their psyche in regards to those other-worldly events. A good example of this is when an author is interpreting events that involve a certain personage whom, for whatever reason, they have a strong personal and/or ideological dislike for.

Specific examples of this (as helpfully provided by my fellow creative mythographer Salvatore Cucinotta) include "Real" Universe [RU] author Alan Moore's attitude towards James Bond, and the situation regarding Cassandra Cain (a.k.a., Batgirl III and the contemporary Black Bat) under some of the authorial and editorial aegis of DC Comics in the RU.

Certain organizations or nations that have counterparts in the RU can likewise be subject to this personal bias taint when filtered through the perceptions and interpretations of certain authors. This explains the very frequent one-dimensional portrayal in American popular fiction of agents working for the government of the Soviet Union during the first few decades of the Cold War. Compare that to the contrasting degree of nuance provided for the Soviet spies in contemporary period TV shows like The Americans.This type of personal author and publisher/producer bias was even more glaring in the "black and white" portrayal of almost any agent or individual employed by or associated with the German or Japanese government during the World War II era; a casual perusal of many comic book covers published in America between 1940 and 1945 will provide eye-popping examples. The contrasting canonized and romanticized portrayal of almost all American soldiers or government agents during that same period was equally glaring, as evidenced in not only those same comic books, but popular American films of the time such as So Proudly We Hail.

Of course, the above situation is also contingent upon how presentations of nuance and depth in general are considered palatable in any given era. This is why in more recent decades, even those considered the designated "enemy" of American values are treated in a more three-dimensional, and thus arguably accurate manner, to the "actual" events when depicted in any given medium. Even in stories or movies, etc., purporting to chronicle the life of individuals and/or organizations that are/were extant in the RU are embellished and subject to these authorial and era-centric biases. For example, several details are said to have been fudged in the film Hoffa to romanticize and ethically sanitize the titular personage of Jimmy Hoffa, so as to make him appear to be mostly devoid of the unscrupulous aspects of his real-life actions, e.g., actually collaborating with organized crime figures voluntarily, rather than resisting their attempts to encroach upon the unions as depicted in the film.

Anachro-centric Biases: This is similar to the above, but is distinguished by a marked focus on time. Many authors want their protagonists to be likable and accepted as heroes by the audience of their indigenous time period. This is sometimes a market-based consideration at least partially insisted upon by publishers and/or producers who provide the resources to put the alternate reality tales of these characters to paper or celluloid in our reality. In other cases, they are based on a variation of an author’s translator bias, as described above.

Here’s the thing about heroes: Many—though certainly not all—must be expected to be subject to the same biases, assumptions, and cultural loyalties as the average person who was born and raised in their specific era and culture. Hence, it’s perfectly logical for a hero living during the Victorian era to have had pronounced sexist attitudes, or to have certain arrogant racist and nationalist attitudes. Yes, there obviously would have been heroes—and even villains—who had enlightened attitudes that were ahead of their time. But we can’t expect all of our heroes to be above the attitudes of the time, because that would be romanticizing them to a highly unrealistic degree.

However, many contemporary authors who write period tales about these heroes (and villains) will slyly tweak their natural biases so that they instead display attitudes more in harmony with those they know most of their readers and publishers/producers will have today. This can result in an Alan Quartermain who incongruously displays sympathies for the then-fledgling women’s suffrage movement, or another British hero like Raffles who openly argues against the “righteousness” of British colonialism. Or, less severely and incongruously, having these no-longer-acceptable-but-once-normative attitudes either downplayed or omitted altogether.

Anachro-centric biases can be even more glaring in tales that occur in various alternate future timelines. This is why we will see future timelines which assume that the economic system, cultural mores, and dominant lifestyle choices of today will live on forever, as if they are fixed in nature instead of products of a specific time.

This is often evident in the Star Trek Future Timeline, which purports to have achieved a far better society free of want and poverty, yet provides conflicting accounts as to whether money and barter still exist or not within the bounds of the Federation; purports full equality between men and women, yet still depicts women taking the last names of their husbands after marriage; presumes that monogamous marriage and the nuclear family unit will remain completely intact as we know them today despite the supposed lack of the same socio-economic factors that caused them to rise during the present era; stories produced during the 1960s insisting that white men still dominate all command positions; people apparently never dating outside the racial, gender, and age boundaries expected by society at the time; and, of course, the presumption that youth liberation will never happen, even to the point of depicting youths as still being predominantly dependent upon their parents in a supposedly better economic system until they are (you guessed it!) exactly 18 years old.

Now granted, a depiction of a future that does not put forth a study of the values of the era in which it is produced would be less compelling on many levels to a contemporary audience. Nevertheless, the assumption that many aspects of our present day societal norms and the current global order will never change is a certain type of wishful thinking that is designed to appeal to modern aesthetics and concerns. I do not agree that it’s impossible to provide a good analysis of the concerns and issues of the present by depicting a future timeline where we achieved a higher form of society. In many cases, the Star Trek franchise did indeed provide enlightened thinking that are not practiced by society today, which elicited much insights to the contemporary mind by way of such a contrast.

Note, for example, the very non-contemporary but highly enlightened way Captain Picard has Geordie LaForge deal with the perpetually nervous and late Reginald Barclay. As another example, note the refusal of Captain Janeway to kill a huge spatial life form that was attacking the Voyager for strictly instinctual reasons, and willing to risk the safety of the vessel to find another way to deal with the problem.

Obviously, there are some alternate future timelines that are dystopic, and where we can expect many of the cultural mores endemic to the present system to continue and even become more pronounced (e.g., the Blade Runner Future). Thus, the frequently perceived need by authors and publishers/producers to make characters and their situations in all of these alternate futures both relatable and acceptable to modern readers in many cases is something creative mythographers need to consider when researching tales that occur in alternate futures. The continuation of such modern cultural tropes and preferences in purportedly more socially and economically advanced futures should therefore be considered suspect, because they may be included simply to provide a greater degree of appeal to the sentiments and comfort of a modern audience.

Red Tape: One of the realities of published and produced storytelling in our present day world is the godly power of copyright patents. This means that certain crossovers between two different characters and/or groups who are recognized by creative mythographers as co-inhabiting a shared universe often cannot be depicted “as occurred” if their fictional representations in our universe are owned by separate companies and/or independent owners.

This doesn’t mean that these crossovers aren’t occurring, of course. It simply means that for legal considerations extant in our world, recorded translations of such meetings must oftentimes be tweaked to minimize or downplay the contact that “occurred” between the two separate parties, or to “disguise” one of the two behind a pastiche or code name. Or to deliberately avoid recording any such crossovers, particularly if the owner of the character copyright in our world has a strong dislike for the crossover concept.

The factor of Red Tape, as its name suggests, can often make it difficult for competing parties in our world to come to an agreement so as to allow one or more authors to record crossovers when they ensue, at least to allow depiction of characters and groups under their actual names with no tweaked details. In fact, it often encourages authors to deliberately tweak these details so as to create the implication in viewers/readers from our world that certain characters or groups exist in an isolated or “purist” universe that contains no anomalous individuals or forces other than those specifically introduced by the owning or authorized authors.

Examples? For starters, note that for copyright reasons, Vampirella couldn’t cross over with Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but had to meet “Fluffy” instead. If one posits that this story was canonical in a universe shared by the two, then this parody-cum-pastiche of Buffy Summers had to have been tweaked to differ sufficiently from the horror hero whose patent is owned by Joss Whedon in our universe. In fact, with this conceit one may surmise that the more parody-like aspects of Fluffy and her crew were add-on elements that didn’t “occur” in the “actual” events.

For another, it should be noted that the only time events where the Golden Age version of Batman ran into Doc Savage and the Spirit could be recorded for readers in our universe to see was during a time when DC, which owns the copyright for Batman, also had a license to legally use non-pastiche versions of both the Man of Bronze and Will Eisner’s masked crime fighter.

Importantly, it needs to be noted that some creative mythographers have understandable qualms about the applicability of the "Anachro-Centric Bias" towards stories that take place in alternate futures, because they feel the standard of evidence required to make it clear that these biases are likely just aren't there. Hence, to quote one of my colleagues in criticism of this, "How do you establish evidence for making any case of that sort? Without evidence, there's nothing to be said but 'this might be incorrect, but I have no evidence standing against it.'"

In respect for this concern, this is what I have to say about this matter:

The

evidence possibly in favor of its applicability may be circumstantial to a large degree, but IMO

nevertheless crucial. That leads to the 'Historical Precedent' theory,

which contends that throughout history, certain types of changes in the realms

of social and cultural mores have accompanied certain types of

socio-economic systems and various types of changes in the cultural structure of

society. Further, and more importantly, change in various social

statuses, attitudes towards various minority groups by the majority,

degrees of freedom and equality amongst the various groups of people in

society, etc., in accordance with these socio-economic and cultural changes has been the observable norm with the passage of time.

Hence, when you observe changed circumstances in an alternate future, but see so

many attitudes and social statuses from earlier systems and eras being

retained (e.g., social inequality between the genders, races, and age groups; monogamous marriage and the nuclear family unit as the norm; women continuing to take the last names of their husband following a monogamous marriage, despite great changes and advancements in the cultural and socio-economic landscape) then I think that is reason to suspect a specific type of bias

in the author's interpretation. This, as noted above, is done for the purpose of sculpting many details about that

alternate future and prominent characters living in it so as to make them philosophically

relevant, synthetically relatable, and socially

acceptable/likeable/redeeming to the audience of the time period it was

written for.

A

further precedent for this is how we have routinely seen authors of one

era change details of characters, situations, and attitudes that we

know to have been true in past eras to make them palatable, reltatable,

and likeable to audiences of the present. Due to this phenomenon being

readily observable, to me it makes no sense to assume this wouldn't be

applicable to stories that take place in alternate futures; or that the

simple fact that we cannot yet observe the "actual" future means that

almost everything we see depicted in an alternate future when it comes

to social conventions, economics, etc., to be taken totally at face

value. This is especially true when we can observe contradictions of

these relevant details between different stories chronicled by different authors that

supposedly take place in the same alternate future timeline.

Note, for example, the very different description of economics and, to some extent, social conventions in the late 23rd century of the Classic Star Trek Timeline as described by Vonda McIntyre in her novels Enterprise: The First Adventure and The Entropy Effect, and their depictions in both all of William Shatner's Star Trek novels and the majority of episodes of all the TV series... except for the odd contradictions here and there, depending upon who was writing a given episode. That alone provides what I believe to be some evidence that this bias towards stories taking place in the future are every bit as applicable as those occurring in the past. You can discount these different sources as occurring in alternate universes, true, but then that brings up the question as to why the type of society we see depicted within each contradictory source is otherwise indistinguishable. Then we see the contradictions in seemingly minor details like Kirk's age when he first took command of the Enterprise as "the youngest captain in Starfleet" depending upon the source in question. This could be a simple story error, or it could be an interpretive bias by the author looking at matters from the standpoint of a person born and raised in the social conventions dominant between the late 20th century and early 21st century. I think this constitutes some evidence in favor of the "Anachro-Centric Bias" in regards to its applicability to stories that take place in alternate futures, but no one in the field of creative mythography is obliged to agree, of course.

How

do we know what "really" happened, then? The truth is, we don't. And we can't. We can

only speculate and theorize, and admittedly most of us (yes, including

me) will be inclined to pick the option that most fits with our own personal

visions of "the future" or a certain conception of social justice, preferences, etc. The same regarding details

in the past that are recorded by authors writing from the present day

vantage point.

Please note that there is nothing in this article that says that everyone who works in this sandbox has to accept my speculations and suspicions, etc. Further, everyone is free to apply them or not apply them as they see fit to any given situation or source we happen to research or analyze. This article and my suggestions were, again, just a series of speculative theories that this author personally consider relevant and valid, and which I hope can provide readers and other creative mythographers with food for thought. Nothing more, nothing less than that.

Topical Details: Topical details are usually deliberate tweaks added by a writer or artist to make an event that “actually occurred” in one time period appear to occur in another era, sometimes removed by several decades, or less commonly, even several centuries. These details can include a faux depiction of fashion, technology, popular slang/colloquialisms, references to pop culture and historical events, and even story tropes that are designed to make a series of events appear current to readers at the time they were published, when in “actuality” they may have taken place much later in time.

The use of topical details is most commonly inserted into events that are published in our world via a Sliding Time Scale depiction. These details are not unique to stories introduced on a Sliding Time Scale basis, of course. For instance, a notable series of examples are the details added or left out of the Carl Kolchak stories published in both prose and comic book form by Moonstone to make it appear that those exploits occurred during the 2000s, when in “actuality” creative mythographers have posited them to take place in the 1970s, when the classic TV show was aired (so ignore those word processors and cell phones!).

Sometimes, of course, this comes down to what any given writer prefers. It can be accepted that there are different alternate reality versions of Kolchak, to continue the example, who operate in different time periods in different realities. But when working from a conceit that that all of his recorded exploits across different mediums occur in the same universe, then one or two things must be done:

1) It’s posited that the Kolchak from the later prose and comic stories is a relative of the original;

2) The original medium of the character’s appearance is taken as the more authoritative source material, and the later stories from a different medium are tweaked to accommodate it.

The evidence must be weighed to suggest which works better, of course. In the opinion of many creative mythographers, including this author, however, the evidence that these are two separate gentleman named Carl Kolchak from the same family just isn’t there. Hence, the second explanation gained favor.

Additionally, as my colleague Kevin Heim noted: "Likewise the topical edits of adding modern technology to a modern storytelling that perhaps belongs in an earlier era also explains the authorial bias of villainizing [if that's not a word, it should be! - CN] a character in an earlier era who was previously treated as a hero in that era due to social standards changing."

This is a good point to consider, as an author will often interpret events or ethical alignment of a character, organization, or even situation based upon what was considered socially acceptable during any given era. Even if an author has a desire to interpret events in an "actual" nuanced fashion their publisher, editor, or producer may demand a less nuanced interpretation to adhere to both their own and perceived audience preferences and expectations. A good example of this is the manner in which stories depicting lesbian romances in literature of the 1950s were interpreted as being inherently doomed specifically because they were same sex romances, and the motives and final fate of the male homosexual character in the play and filmed version of Suddenly, Last Summer was interpreted as they were.

Ethnic, gender, and age-centric topical biases also include the way black characters were depicted in comics prior to the late 1960s and 1970s. For instance, was the highly stereotypical depiction of the Spirit's friend and sidekick Ebony in the comics of the 1940s and early '50s truly "accurate"? I would argue they were more likely topical characteristics added to make the character adhere to what RU audiences expected. The same can apply to the servile and "weepy" attitude of women depicted in comics and films of the time, even in tales that supposedly took place in alternate futures. Contrast that to the personality and actions of horror hero Ellen Ripley in the Alien franchise of films produced--and therefore "interpreted"--between the late 1970s and early '90s. Finally, note how the ageist portrayal of the Legion of Super-Heroes in their earliest appearances circa late 1950s, had them acting obediently servile to adult authority despite defeating galaxy-threatening menaces while often relying upon their own strategy and decisions. The topical references described in the above two paragraphs tie in with Translator Bias and Anachro-Centric Biases detailed elsewhere in this article, but can also be attributed to Topical Details. Like characters themselves, errors can sometimes straddle different categories.

An important form of topical detail are those attributed to dating of events. If one works from a conceit that in the Wold Newton Beyond Universe [WNBU], Spider-Man’s history operated in “real time” on a generational basis, and the Sliding Time Scale common to comic book companies like Marvel and DC is rejected, then the original publication date of his first appearance (1962, Amazing Fantasy #15) is considered authoritative regarding his first appearance. In this case, the era-specific details seen in the decades when the comics were produced are not considered topical, but accurate. Instead, tweaking to the details regarding the nature of the events needs to be done, since the generational approach cannot have Peter Parker remain active as Spider-Man for 50 years.

Translation Errors: Filtering psychic records of events that are purported to “actually” occur in often quantum-vibrationally distant alternate realities can be difficult. This is true for even some of the best and most creative authors and producers, whose minds are most apt to “pick up” these events.

Because of the filtering process that occurs when these events are translated into words and/or images on paper or screen in our world, misinterpretations of certain details—most often but not always little things—can creep into the records. These run the gamut from errors in accurately interpreting dialogue, mistaking the actions of one character for those of another, and making incorrect guesses as to the exact time period or sequential order of recorded events.

Why should we presume this is the case in many instances? If we assume the dialogue is always depicted on page or on screen exactly as it was “actually” said in the alternate universe event being translated, then we must consider the idea that profanity was used far less often in that universe, even when people were very angry. Or, that spoken dialogue was conveyed in dramatic, histrionic ways during certain eras of that world’s history, when such was only the case in movies or stories in our own reality. Could this be true? Certainly, but whether we accept it as completely and literally accurate or not depends on whether we work with a conceit that the other universe is culturally and linguistically close to our own.

This is to be expected due to the common tendency for humans to flub details they see and hear with their own eyes, let alone those that they perceive “through the ether”! Further, as a corollary of the above described Translator Bias, some translation errors are done deliberately. For example, dialogue can be altered from what is “actually” said by the alternate reality parties in question to fit the aesthetic preferences or requirements of both an author and publishing or production company. To provide two common examples, these “deliberate errors” can take the form of eliminating profanity to assuage audience sensibilities, or to use a style of rhetoric more in tune with audience expectations of a given place.

Hence, in many cases what we see characters saying will represent just the general idea of what they were “actually” saying, as is the case when dialogue from foreign films is sub-titled or dubbed from one lingo to another.

Technical Errors: These types of errors aren't so much related to either deliberate or accidental interpretive biases on the part of the author, but based on the same type of mistakes made on non-fiction books or documentaries when it comes to matters related to formatting. This can be the result of a language barrier obstructing a translation of events and/or dialogue, or simply poor printing skills and/or neglect in the printing procedure.

As my colleague Salvatore Cucinotta noted regarding the two major forms that Technical Errors often take:

"Copy-Edit Errors are another type worth noting. In translating or 'copying' a document or any source, errors can and will occur. There are copies of The Bible in the Vatican which even have notations written in them from the same time period chastising the text for misprinting certain passages.

"And then there's Actual Translation Errors. Many of the stories come to us in English but may not have been spoken in that language originally. Modern English didn't really develop until roughly the time of Shakespeare. On top of that we have stories that may be written all in rhyme scheme or iambic pentameter. In some circumstances that can be accepted easily enough, but those are rare."

***

The above list is by no means exhaustive, but is designed to give a basic overview of the most common reasons to question what we see or read when it comes to the “reality” behind fictional events recorded in our world’s literature and cinema. Doubtless additions and revisions will be added to this work in the future, some of which will likely be suggested or identified by other authors in the field of creative mythography.

It should finally be noted that this work deliberately excludes recordings of events that represent mistranslations conducted by various individuals or organizations within the context of a given alternate universe itself.

This doesn’t mean we should never assume that the general series of events and conversations we saw on page or on screen didn’t “occur.” Rather, we should keep in mind that events from alternate realities/timelines are filtered through the imperfect perceptions of human beings on our side of the quantum barrier, and hence are subject to all of the error categories discussed above.