[A Third Optional Addendum to The Pretentious Paper]

By James Bojaciuk

Contact:

powerofthor2011[AT]gmail[DOT]com

Once upon a time when gaslights still ruled London, the Master Detective and the Napoleon of Crime tumbled down Reichenbach Falls. What arose from the Falls in the coming days, as news spread by telegraph and newsprint (as yellow as the written reporting therein), was a cloud of dismay. Black armbands and black gowns were London’s style for months. They had lost their hero. Crime skyrocketed without the Master Detective to keep it in check; for the first time in years, there were unsolved murders.

Under cigars held aloft and above double-malt whiskey, the men in London’s most secret club smoked and drank and talked, working through a solution. They did it properly: With thought and care, mapping plans out on sheets of paper which may still be seen in their archives.

This group was not the Diogenes Club. Not at all. The Diogenes Club was ruled by the one man in all Europe who knew the late, great Sherlock Holmes was not as late as supposed.

No, this was another club, one more secretive even than the one ruled by the man who was, on occasion, the British government itself. This club did not have a proper name. Sometimes they called themselves the publishers of Venom Feels Delightful Press (an outfit rivaled only by the Cannibal Club in ranks of ribaldry); at other times they were the Volunteers Fighting Disease (wandering through London’s hospitals with songs and sweets); and, on their larkiest days, they called themselves the Volunteer Fire Department, though they could never be caught hushing a single flame down into embers.

Only the three letters consistently followed them, the V, the F, and the D. If they had any deeper meaning, the masters themselves were unaware.

Their club members stretched from Her Majesty’s cabinet and maids to the drunk, to the second drunk on the left, just outside the shoddiest dive the East End had to offer. The police force was riddled with their men, just as one out of every three men in Moriarty’s former empire could be said to listen to the three-lettered cabinet as much as they listened to the Professor himself. They were not quite a conspiracy, they were not quite a cult, but they were certainly men who wished for Change. The VFD wished—and perhaps still wishes—for the world to become quiet.

Thus the VFD had their problem: The wisest man they had ever heard of was dead.

Thus, through their plans and pipe-fog, they found their solution: Rise Sherlock Holmes from the dead like the Phoenix. They could not reanimate his body. But what they did have was the sole thing that London had in abundance, and that was orphans; better yet, starving orphans desperate to do any required thing to improve their station in life. Their leader, Andrew Myatt, is reported to have remarked on that long ago evening, “Train boys in the way they should go, and no matter how improbable, they shall not depart from the truth.”

And so it began.

The VFD purchased a manor in Winchester. With the carpenters, gasmen, and workmen in their league, they swiftly established a modern marvel. Tests were promptly carried out in on the orphan population in London. The most promising students were collected and brought to the school, where they were kept under strict watch. It’s interesting to note that the VFD made no differentiation between male and female students. Both sexes were freely accepted.

The VFD’s school was built upon a solid physical foundation. Now all they needed was an intellectual foundation, i.e., a professor.

Much has been made in Sherlockian scholarship of the man known as Sexton Blake. Nearly a century after his zenith—which even then was obscured behind the Master—we still do not know details of his family, his life, or his death. We do not even know his true name. All we have are his cases—and the familiar image of a man who could look in the mirror and find Holmes’ face.

Here, when the VFD sought to restore the memory of Sherlock Holmes to life, we come across a very curious fact. Sexton Blake’s first reported cases appeared in 1893, two years after Holmes’ reported death. Blake was a muscular man of massive build, but not at all tall. Yet, the very next year, as soon as he was established in London, he suddenly transformed from a powerhouse into a Holmesian detective: hawk-faced, tall, and lean.

For the right price, a man may change his very appearance. Blake needed fame; the VFD needed a professor. When classes commenced, the Blake who entered could hardly be told apart from Holmes. He was a bit taller, a bit more muscled, but he was no longer the bruiser he once was.

With what Watson had written of the canon, with all the works of modern criminology, with all the aid of the best investigators in the land, Blake set to teach the VFD’s children. It was a disaster. They were trained to abandon emotions, to keep their thought-attics sparse; to become, in short, a child’s glossed conception of Sherlock Holmes. Each student had the Holmesian veneer—the pipe, the surgery-assisted hawk-profile, the infernal deerstalker which the Master himself never wore—but they lacked Holmes’ core.

The students, in general, could typically solve nothing. The student who came closest to passing was an exceptionally short street urchin named Alexandra Machita. She was brilliant enough to be a Poirot, or if mentally stretched, a Father Brown—but she could never, ever, be a Sherlock Holmes. Another student, one Edward “Tinker” Carter, was significantly less astute. But he made an impression on Blake, so that through the coming decades he would be his most loyal associate.

Blake insisted it was the VFD’s fault; the VFD insisted it was Blake’s fault, and that now, 20 years had been wasted. Two decades during which the world had changed and Sherlock Holmes had returned from the dead. Blake asked for one final chance to nurture a new batch of students from which he would build legends. All he asked was that he could restructure the curriculum. Or, perhaps, a better way to put it is this: He asked to violate the curriculum and build the school into something that had never before been seen.

And so the VFD’s great experiment began in earnest.

With the coming of the new class, we may introduce the next of our extraordinary documents:

The works of Lemony Snicket. Snicket, at press time, is in his 90s. He is ridden by an ever-worsening dementia. When he began his life’s work in 1999, with the book his publisher titled A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Bad Beginning, it was a sober account of the war that destroyed the VFD in the 1960s. As the accounts progressed, and Snicket’s dementia worsened and worsened, they verged on the impossible. They included squid-like submarines rowed by kidnapped children, secret islands of outcasts within a few days sailing from Los Angeles, and small towns ruled by old men who wore stuffed ravens on their heads. But Snicket is one of the very few members of the VFD to have broken the bonds of silent trust, so we must rely on him, even as he descends into insanity.

As Snicket tells us without daring to name names, Blake established new stratagems.

All students would be “kidnapped” by agents of the VFD. Sherlock Holmes suffered a trauma in his youth (though the latter-day biographers could never quite decide if his mother had had an affair with the future Professor Moriarty, or if his father had killed his mother, or if both were true. Watson knew; but he never told, not once). It would be best if the prospective students suffered just as much of a trauma—finding themselves yanked from their beds in the middle of the night, a sack pulled over their heads, and dragged away to school. Their parents would know, of course. There’s no reason to go about committing crimes. Snicket nearly cracked when this happened to him.

The Snicket kidnapping—if we may go out on a tangent—was such a scandal it fueled folk songs for decades. Among the most famous of these was “Robber Road,” a song which reveals quite a bit of VFD methodology.

When we grab you by the ankles,

Where our mark is to be made,

You’ll soon be doing noble work,

Although you won’t be paid

When we drive away in secret,

You’ll be a volunteer,

So don’t scream when we take you

The world is quiet here.

But all songs fade, no matter their truth. The new students were taken at night, the north wind the only witness. They were tattooed with the insignia of the VFD, the three letters so artfully contrived so as to depict an unblinking eye—“the detective’s eye,” Blake would say—and found themselves without pay (arguably the worst part of the whole affair).

All students would be stripped of their identity and given a single letter as identification. In the olden days the letters represented the first letter of their first name. Thus Lemony was L, his love Beatrice Baudelaire was B, and the infamous actor “Count” Olaf Murdstone was O. In the latter days, once the Schism between arms of the VFD had passed away, the letters lost all connection to reality. You cannot be traced if your letter bears no resemblance to your name.

All students would be trained extensively in the Holmesian arts. It was a strange state of affairs for a school dedicated to replicating Holmes to have so few classes dedicated to either his own philosophy—or his own non-essential accruements to the art of detection. Snicket’s dementia-ridden Unauthorized Autobiography details the lengths to which the VFD went in replicating some of Holmes’ feats. Every student was to own a disguise kit containing no less than 60 items, including a full theatrical stage make-up kit. When they became graduates, each former student was required to have at least one (though more was ideal) hideaway for performing quick transformations. As Watson wrote in “The Adventure of Black Peter,” “The face that several rough-looking men called during that time and inquired for Captain Basil made me understand that Holmes was working somewhere under one of the numerous disguises and names with which he concealed his own formidable identity. He had at least five small refuges in different parts of London, in which he was able to change his personality.” This, they could duplicate.

Additionally, each student was to know a full smattering of codes, from the obvious to the impossibly obscure. What Holmes figured from cold intellect (see “The Adventure of the Dancing Men”) the students were to know cold before any cypher’s creation. An impossible goal, perhaps—but such things did not overly concern Blake. This time, the students were producing results.

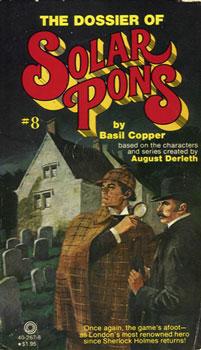

Indeed, this class produced one of the greatest of the detectives who followed in Holmes’ footsteps: Solar Pons. He did not reside in Baker Street, but in nearby Praed Street (for, in those early days, the Master still owned his old lodgings). Pons was the best of the best—and in those early days of Holmes’ retirement, he filled a role in society that was essential to the continued order of London. More importantly, to the VFD, he established the beginnings of the traditions expected of the man the VFD named the Sherlock Holmes: He took up residence in a place much like 221 Baker Street (which would later be replaced with a residence in 221 itself, once the VFD purchased it); become friends with a medical man of literary pretentions who chronicled his cases (and had them published by a literary executive, in this case August Derleth); remained a private detective with no official ties to the state; and remained free of the drugs which soiled the first half of the Master’s life.

Pons, in some slight regard, is directly responsible for the popular image of Sherlock Holmes. What Sidney Paget and William Gillette began--Paget gave Holmes the deerstalker and inverness when Holmes stepped into the country; Gillette gave Holmes the calabash pipe--Pons finished. He could not be found without the deerstalker, without the inverness, without that peculiar pipe. This gave Universal Studios the image they needed, when they adapted some of Pons’ otherwise unrecorded cases to celluloid in the celebrated series of Rathbone/Bruce Sherlock Holmes films. [1]

Pons served as the official Sherlock Holmes of the VFD until the late 1950s, when he retired to peaceful composition in the Welsh highlands.

Before the next Sherlock could be selected, all Hell would come forth. The event that Snicket called the Schism erupted, tossing all VFD agents into two sides. They can be loosely defined as “the VFD that set things on fire” and “the VFD that put fires out.” But then, those are flawed definitions. They suggest one VFD was morally better than the other, when both employed murderers and madmen—and saw nothing the matter with taking the lives of children.

The full story—or even a sketch—of the history of the Schism is far outside the scope of this article. [2] It may suffice to say that it ended, but only through the efforts of the Baudelaire orphans. The VFD was decimated, but there remained enough men and women of vision and insight to reinstate the programs deemed most necessary. Among those programs was the training of a new Sherlock Holmes.

They proceeded to rebuild. The first students, none older than five years of age, were admitted into the rebuilt and expanded Wammy’s House in 1986. Three students excelled above all others: L, J, and B.

But there was another Holmes in those days. And she lived at 112 Baker Street, holding court over all the Punk Quarter of London.

She was Sharon Ford, the Harlequin. Her story begins and ends in question marks. We do not know from whence she emerged, for she appeared in London fully formed. Some of the old punks suggest she was a cop, a street beat walker, but that’s the merest whisper of rumor.

She solved crimes. She owned Holmes’ own inverness, which she rarely removed. [3]

In her flat above Hudson’s Book Shop (no relation to Holmes’ own Mrs. Hudson), she resided with her girlfriend Sam (who was actually a male prostitute who identified as a woman, yet didn't identify as a cross-dresser or transsexual, either pre- or post-op), and their frumpy, conservative live-in secretary Susan Penderghast. Sue was Watson, in this scheme. They hunted a modern revival of Jack the Ripper (who, in turn, only hunted men), and tracked down other killers.

Then, Sharon disappeared. No one has heard from her in 30 years. No further published accounts have surfaced, under Penderghast’s pen or another’s. No newspapers have spoken of her. As mysteriously as she appeared, she disappeared back into the shadows. One wonders if we’ll ever hear from her again.

Now we return to the VFD, and their special ones. Starting with their star, L.

L was special, the most exceptional student to graduate the program. Every other student, including those honorarily given the Master’s name, are but a candle held against the Sun. L had the potential to be a sun. He was already a spotlight. We have no true accounts of his life. He perished while tracking a serial killer in Japan. We do not even know how he died. There were no marks on his body—no trauma, no suffering, just a brilliant mind ushered into the unknown. His life story was bought by a manga company and written as Death Note. It is a highly inaccurate retelling, however. An unknown serial killer is given a name and backstory; L is nearly reduced to a madman who collects his mental powers from eating an unending stream of cakes and candy; and, perhaps worst of all when telling the story of a young man who fully believed in Holmes’ maxim that “No ghost need apply,” the active agents behind the killer are demons and monstrous grim reapers. Perhaps one day L’s story will be truly told.

The saving grace of the series is the few factual glimpses it gives us into the world of the VFD. Each member, as Snicket stated, has their identity reduced to a single arbitrary letter, and they were recruited as children and trained in the art of detection by an assortment of past graduates and the greatest modern minds. It confirmed, once and for all, the existence of the VFD beyond the days of the Schism.

But L was dead, decidedly dead in fact, and not likely to rise up from his own fall.

The VFD scrambled to find his replacement. And so they did, in the person of J. He was the son of a billionaire, snotty and brilliant, and more than willing to inform anyone who was unaware. He was not quite a leader. He adopted the scarf-style B had begun, and a dozen more stylistic tics besides. J’s genius lay in following to a point, then turning sharply aside. It was his game.

J became the Sherlock—but he committed four unforgivable sins against the VFD, four sins which led to his dismissal and exile.

221 Baker Street was his, from the 17 steps to the wall which still bore V.R. in bullet pocks (now tastefully hidden behind a Claude Joseph Vernet original). The Persian slipper resided beside the jackknifed correspondence and the gasogene. Every piece of the Master’s home-life was well organized, ready for the new Sherlock to take it up. But J never lived there. He preferred a little hole in the wall lost in the twists and back alleys of the East End. And thus he committed his first sin against the VFD (three more to go).

As the Sherlock, J was expected to befriend a medical professional of frustrated literary pretentions. Or, at the very least, someone with a name that half-way sounded like “Watson.” Watkins would have been acceptable, or even Dawson. Instead, he found no-one. He worked alone, the gaunt man in the corner with the eyes that could only belong to Sherlock Holmes. And thus he committed his second sin against the VFD (two more to go).

The VFD forgave him, of course. For the first time since the beginning of the conspiracy, they had established a true heir to Sherlock Holmes. He solved all cases set before him. The Golden Age of Baker Street threatened to come again. But then came the London Tube Bombing. J was a moment from solving it, from preventing the flames and twisted metal and souls stolen by the north wind’s gusts. The spooks had come for his brain too late, too late. Private detection was swiftly abandoned, and within a month he was a ranking member of London’s anti-terrorism squad. And thus he committed his third sin against VFD (one more to go).

Then came his torrid romance with the woman he called Irene, after the Master’s own Irene. Then came her death at the hands of the London godfathers. Then came J’s descent into drugs, homelessness, and failure. The final straw, for his masters, was to witness him give into heroine. Only one Holmes could give into its temptations, as far as they were concerned.

The VFD exiled him in 2009, and he left the fold in disgrace. They took his right to the very title of Sherlock Holmes. [4]

As of now, he lives in New York City and—having finally taken a medical professional named Watson as his sidekick—works with the NYPD to solve cases worthy of his namesake. But, still, he is the prodigal son who will not be allowed to return.

A new Holmes was required. One without the necessary emotions which could lead to romance and, therefore (in their minds) to failure. B was such a graduate. He was the new Holmes, and he followed his masters’ instructions to the letter. He took up residence in old 221 Baker Street, found a slightly dull but loyal medical man named Watson, remained a private detective, and did not engage in any sort of drugs (beside the occasional nicotine patch). All the better, his Watson wrote a blog, which was then packaged by the BBC into a series of massively popular telefilms. All was as it should be. The Phoenix had risen from the ashes, and there was a Holmes in Baker Street once more--a proper Holmes, with cold wit and ability.

Then he stepped off the roof of a hospital, the corpse of a madman behind him, and B left this life. Perhaps he will return as the Master did, so long ago.

But, for the first time in a century, there is no Holmes in London.

FOOTNOTES

[1] As originally theorized by Prof. Dennis E. Power.

[2] For the full story, see my forthcoming article “The Pretentious Paper: A Series of Unfortunate Events in the Wold Newton Universe.” This paper is an optional addendum to that work.

[3] Sharon bought Sherlock Holmes’ inverness as described in the story published in the one-shot comic Baker Street Graffiti. Someone was selling off the furnishings of 221 Baker Street, and among such trophies as the blue carbuncle, the infamous cardboard box, five well-preserved orange pips, the jackknife with which Holmes kept his correspondence, and so on.

One caveat. If you read about Baker Street online—or read the introduction in the first issue—the authors explain how the events of Baker Street take place in an alternate timeline where WW2 never happened, etc. Except, there is nothing at all in the comic itself to support this. Save for an occasional blimp, there's nothing at all to suggest it takes place outside the 1980s London of the mainline Wold Newton Universe [WNU], as we Wold Newton University scholars refer to the world outside our window. In fact, Adolf Hitler is mentioned in such ways that it suggests WW2 did indeed occur.

If the authors intended to explore the alternate universe of their world, they did not do so before cancellation, which makes it fair game for the WNU.

[4] In Elementary, the latter-day Sherlock states he was thrown out of England in late 2009. In Sherlock, that Sherlock opened his practice in early 2010. It is too neat a “coincidence” to ignore.