By Andrew Lang

Transcribed from the original by James Bojaciuk

This letter appeared, along with a great many other pastiches, in a series of letters prepared by Andrew Lang—the man responsible for those extremely colorful fairy-books. The stories originally appeared in the St. James’s Gazette, but found their way into a slim volume entitled Old Friends: Essays in Epistolary Parody. Many beloved Victorian characters found occasion to correspond, and in their correspondence expand their tales and weave unlikely webs. The volume promises to be a treasure-trove for Wold Newtonian researchers in coming years.

Consider this transcription a whetting of your appetite, if you will.

Here, Herodotus (the Father of History) confers with his friend Sophocles (the greatest of all Greek playwrights) about an unusual nation in Africa. He calls it the land of the Amagardoi. It’s a worthy attempt to transcribe the name (especially at second hand). But, perhaps, we would be best taking the transliteration of another, later man who met the people face to face. He called them the Amahagger.

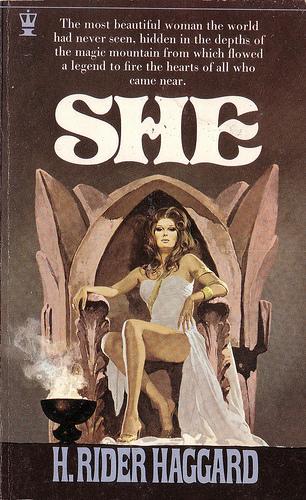

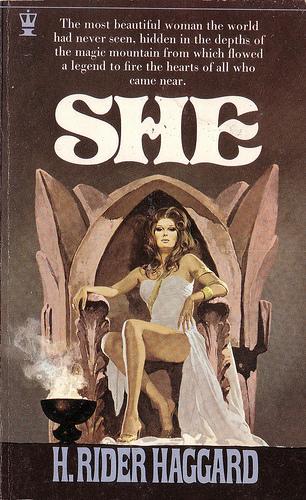

This second man’s name was Horace Holly, the man fated to chronicle the life—or, rather, lives—of She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed, Ayesha. His own adventures are too well reported in creative mythographical circles to require a sketch by my feeble hand. But this letter draws out four important points.

First, that the reincarnation of Amenartas and Kallikrates in the form of Ustane and Leo Vincey was not a singular event. Indeed, Amenartas and Kallikrates were not so much as the first to bear this fate. We cannot even say that the incarnations known to Herodotus, named Nicaretê and Phanes, began the cycle. It reaches back beyond our ken.

Second, the lineage that bound Kallikrates and the Leo Vincey together does not seem to be a lineage of blood. Holly notes that Kallikrates is the son, or perhaps grandson, of Kallikrates the Spartan. Between the two Kallikrates we have nothing but fine Greek stock. Yet, Phanes is a Phoenician. Perhaps Kallikrates the Spartan mated with a Phoenician who produced Phanes who, in turn, produced Kallikrates the second. Perhaps the reincarnation does indeed pass without respect to blood. Presently, we cannot say.

Third, Ayesha is significantly older than presumed; indeed, she’s significantly older than she intimated to Holly and Vincey. One wonders how old she truly was—perhaps she was old enough to remember time-lost Khokarsa and when Opar was still a city of “gold, and silver, ivory, and apes, and peacocks.”

Fourth, in a fit of the coincidence that would plague Tarzan, the following letter was vetted by no less an individual than Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, better known as the father of the Dr. Dexter Flinders Petrie who so ably battled Fu Manchu. (See “Who’s Going to Take Over the World When I’m Gone” by Win Scott Eckert, recently printed in Myths for the Modern Age.)

As for the text below, two eminently large paragraphs have been broken apart to suit the modern Internet reader. Otherwise, the letter appears just as Andrew Lang "translated" it. For the most part, I will leave you, reader dear, to navigate this letter on your own. Here and there, however, Lang could not resist leaving a footnote. Enjoy them at your discretion.

The above title is supplied by the transcriber. The summary below, however, is preserved from Lang.

From Herodotus of Halicarnassus to Sophocles the Athenian

Herodotus describes, in a letter to his friend Sophocles, a curious encounter with a mariner just returned from unknown parts of Africa.

To Sophocles, the Athenian, greeting. Yesterday, as I was going down to the market-place of Naucratis, I met Nicaretê, who of all the hetairai in this place is the most beautiful. Now, the hetairai of Naucratis are wont somehow to be exceedingly fair, beyond all women whom we know. She had with her a certain Phocæan mariner, who was but now returned from a voyage to those parts of Africa which lie below Arabia; and she saluted me courteously, as knowing that it is my wont to seek out and inquire the tidings of all men who have intelligence concerning the ends of the earth.

“Hail to thee, Nicaretê,” said I; “verily thou art this morning as lovely as the dawn, or as the beautiful Rhodopis that died ere thou wert born to us through the favour of Aphrodite.” [1]

Now this Rhodopis was she who built, they say, the Pyramid of Mycerinus: wherein they speak not truly but falsely, for Rhodopis lived long after the kings who built the Pyramids.

“Rhodopis died not, O Herodotus,” said Nicaretê, “but is yet living, and as fair as ever she was; and he who is now my lover, even this Phanes of Phocæa, hath lately beheld her.”

Then she seemed to me to be jesting, like that scribe who told me of Krôphi and Môphi; for Rhodopis lived in the days of King Amasis and of Sappho the minstrel, and was beloved by Charaxus, the brother of Sappho, wherefore Sappho reviled him in a song. How then could Rhodopis, who flourished more than a hundred years before my time, be living yet?

While I was considering these things they led me into the booth of one that sold wine; and when Nicaretê had set garlands of roses on our heads, Phanes began and told me what I now tell thee but whether speaking truly or falsely I know not. He said that being on a voyage to Punt (for so the Egyptians call that part of Arabia), he was driven by a north wind for many days, and at last landed in the mouth of a certain river where were many sea-fowl and water-birds. And thereby is a rock, no common one, but fashioned into the likeness of the head of an Ethiopian.

There he said that the people of that country found him, namely the Amagardoi, and carried him to their village. They have this peculiar to themselves, and unlike all other peoples whom we know, that the woman asks the man in marriage. They then, when they have kissed each other, are man and wife wedded. And they derive their names from the mother; wherein they agree with the Lycians, whether being a colony of the Lycians, or the Lycians a colony of theirs, Phanes could not give me to understand. But, whereas they are black and the Lycians are white, I rather believe that one of them has learned this custom from the other; for anything might happen in the past of time.

The Amagardoi have also this custom, such as we know of none other people; that they slay strangers by crowning them with amphoræ, having made them red-hot. Now, having taken Phanes, they were about to crown him on this wise, when there appeared among them a veiled woman, very tall and goodly, whom they conceive to be a goddess and worship. By her was Phanes delivered out of their hands; and “she kept him in her hollow caves having a desire that he should be her lover,” as Homer says in the Odyssey, if the Odyssey be Homer’s. And Phanes reports of her that she is the most beautiful woman in the world, but of her coming thither, whence she came or when, she would tell him nothing. But he swore to me, by him who is buried at Thebes (and whose name in such a matter as this it is not holy for me to utter), that this woman was no other than Rhodopis the Thracian. For there is a portrait of Rhodopis in the temple of Aphrodite in Naucratis, and, knowing this portrait well, Phanes recognized by it that the woman was Rhodopis. [2] Therefore Rhodopis is yet living, being now about one hundred and fifty years of age.

And Phanes added that there is in the country of the Amagardoi a fire; and whoso enters into that fire does not die, but is “without age and immortal,” as Homer says concerning the horses of Peleus. Now, I would have deemed that he was making a mock of that sacred story which he knows who has been initiated into the mysteries of Demeter at Eleusis. But he and Nicaretê are about to sail together without delay to the country of the Amagardoi, believing that there they will enter the fire and become immortal. Yet methinks that Rhodopis will not look lovingly on Nicaretê, when they meet in that land, nor Nicaretê on Rhodopis. Nay, belike the amphora will be made hot for one or the other.

Such, howbeit, was the story of Phanes the Phocæan, whether he spoke falsely or truly. The God be with thee.

Herodotus

[1] In his familiar correspondence, it will be observed, Herodotus does not trouble himself to maintain the dignity of history.

[2] Mr. Flinders Petrie has just discovered and sent to Mr. Holly, of Trinity, Cambridge, the well-known traveler, a wall-painting of a beautiful woman, excavated by the Egypt Exploration Society, from the ruined site of the Temple of Aphrodite in Naucratis. Mr. Holly, in an affecting letter to the Academy, states that he recognizes in this picture “an admirable though somewhat archaic portrait of She.” There can thus be little or no doubt that She was Rhodopis, and therefore several hundred years older than she said. But few will blame her for being anxious not to claim her full age.

This unexpected revelation appears to throw light on some fascinating peculiarities in the behavior of She.